Carl Jung loved the Africa he knew. When he visited Kenya and Uganda in 1925 he found, in his inimitable way, deep meaning in what, for someone else, might seem insignificant. He had a fine eye for detail and, it appears, an outgoing nature which allowed him an intimate access to the Africans he met. Marveling at the flooding of the world with the rising sun, he felt both a personal ecstasy and the primordial longing for light. And he was overwhelmed when seeing a Maasai laibon (shaman) performing rituals to balance that principal of light – the rising sun, the good – with that principal of darkness – the night, the evil: sprinkling milk and spitting in liminal, vulnerable spaces as a gift offering, the milk, a nomad’s source of life, the spittle, his personal mana.

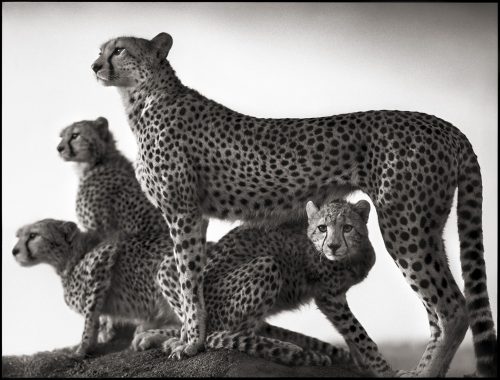

I read Jung’s Memories, Dreams and Reflections during my first long stay on the African plains when we were filming cheetah. Those 12-hour days camped in our vehicle waiting for good shots (we, too, lived the ecstasy and the dread that day and night brought) were blissful hours for reading, and Jung was on our list. On our second return to the bush we lived closely with the Maasai, and the rituals Jung described half a century before were still part of our everyday life. Papai, the elder who lived with us and who became a father to me, dispensed a good deal of spittle on my forehead and shoulders and, when I insisted on moving my tent within sight but out of hearing from his own, he sprinkled milk around the perimeter before he would let me move in.

Jung records a conversation he had with the laibon in ’25. “In old days,” he told Jung, “the laibons had dreams and knew whether there is war or sickness or whether the rain comes and where the herds should be driven.” He meant, Jung says, that since the white man came, no one had dreams anymore. The laibons’ power had vanished. This comment must have been distressing to Jung for whom dreams were the pathway to the unconscious.

I remembered the laibon’s lament about not having access to his deepest self shortly before I departed the bush. After dinner Peter, an 18-year-old town Maasai who lived with us in camp, and I would sit around the fire listening to Papai’s stories. Peter, the child of an oral culture, was mesmerized by his storytelling, and, as my stay drew to a close, I would find him hunkered down under a tree with the old man talking in that murmured cadence I had grown so to love. And then the day before we left Peter had his own lament: “There are no good stories anymore.” Just as dreams were the path back to the laibon’s unconscious, so, too, were the stories Peter’s roadmap to his and his people’s history. Without them he, too, would lose much of his soul.

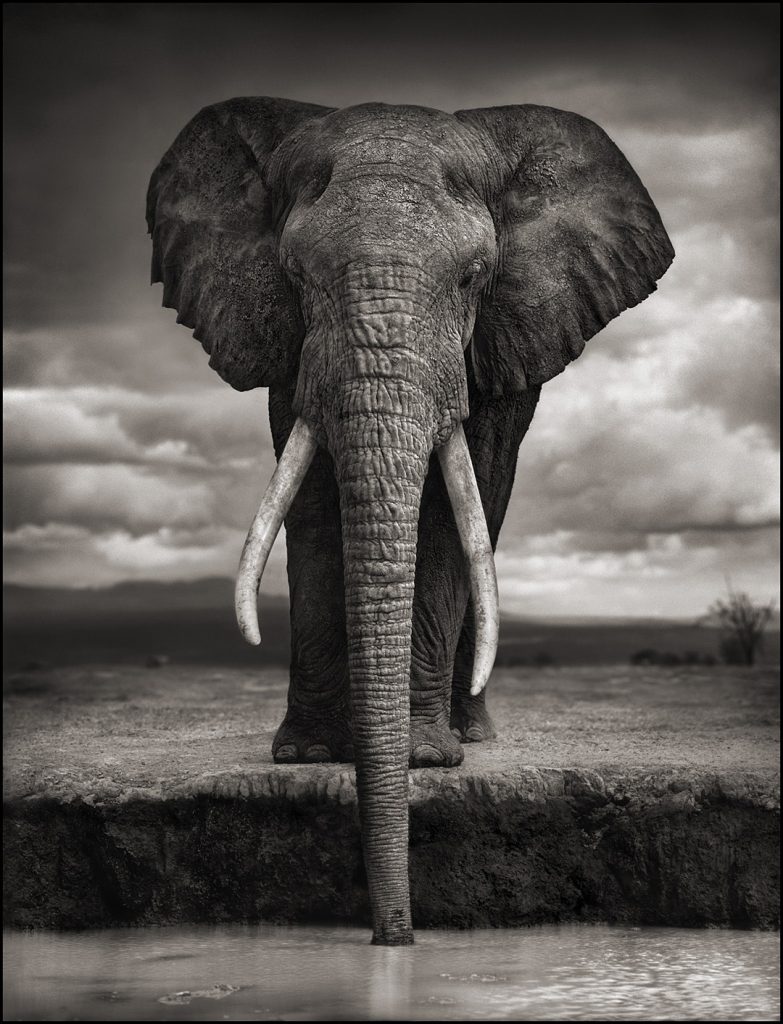

Big Life was co-founded by photographer Nick Brandt and award-winning conservationist Richard Bonham in September 2010.

Since its inception, Big Life has expanded to employ hundreds of Maasai rangers—with more than 40 permanent outposts and tent-based field units, 13 vehicles, tracker dogs, and aerial surveillance—protecting 2 million acres of wilderness in the Amboseli-Tsavo-Kilimanjaro ecosystem of East Africa.

Big Life was the first organization in East Africa to establish coordinated cross-border anti-poaching operations.

THE MISSION:

On the ground in Africa, partnering with communities to protect nature for the benefit of all.

THE VISION:

Envisioning a world in which conservation supports the people and people support conservation.

WHAT BIG LIFE DOES:

Using innovative conservation strategies and collaborating closely with local communities, partner NGOs, national parks, and government agencies, Big Life seeks to protect and sustain East Africa’s wildlife and wild lands, including one of the greatest populations of elephants left in East Africa.

The first organization in East Africa with coordinated anti-poaching teams operating on both sides of the Kenya-Tanzania border, Big Life recognizes that sustainable conservation can only be achieved through a community-based collaborative approach. This approach is at the heart of Big Life’s philosophy that conservation supports the people and people support conservation.

" ["post_title"]=> string(32) "Nick Brandt: Big Life Foundation" ["post_excerpt"]=> string(0) "" ["post_status"]=> string(7) "publish" ["comment_status"]=> string(4) "open" ["ping_status"]=> string(4) "open" ["post_password"]=> string(0) "" ["post_name"]=> string(31) "nick-brandt-big-life-foundation" ["to_ping"]=> string(0) "" ["pinged"]=> string(0) "" ["post_modified"]=> string(19) "2016-11-11 11:30:56" ["post_modified_gmt"]=> string(19) "2016-11-11 16:30:56" ["post_content_filtered"]=> string(0) "" ["post_parent"]=> int(0) ["guid"]=> string(31) "http://lisalindblad.com/?p=6648" ["menu_order"]=> int(0) ["post_type"]=> string(4) "post" ["post_mime_type"]=> string(0) "" ["comment_count"]=> string(1) "0" ["filter"]=> string(3) "raw" } }